Limits of Cost Reduction

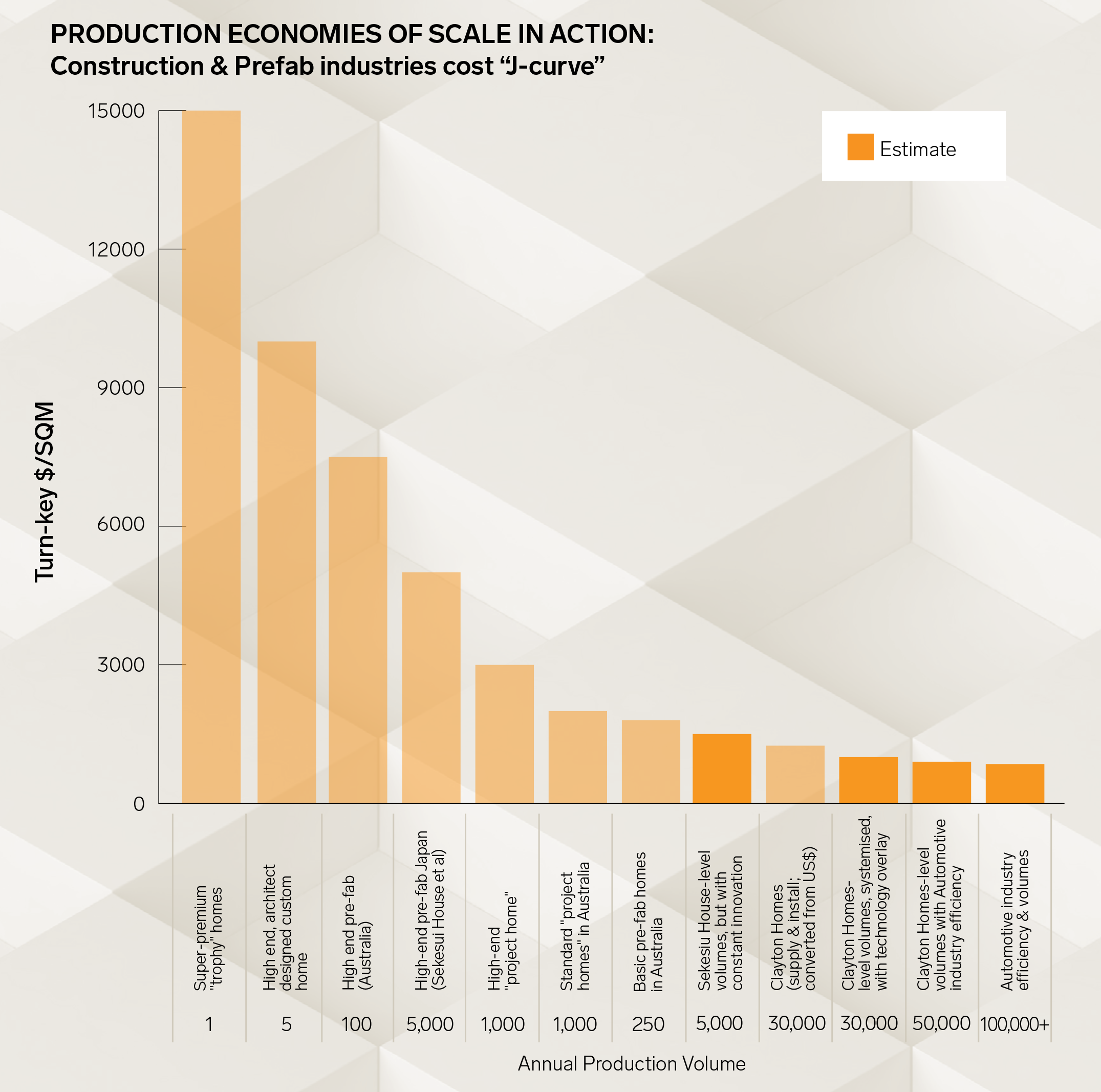

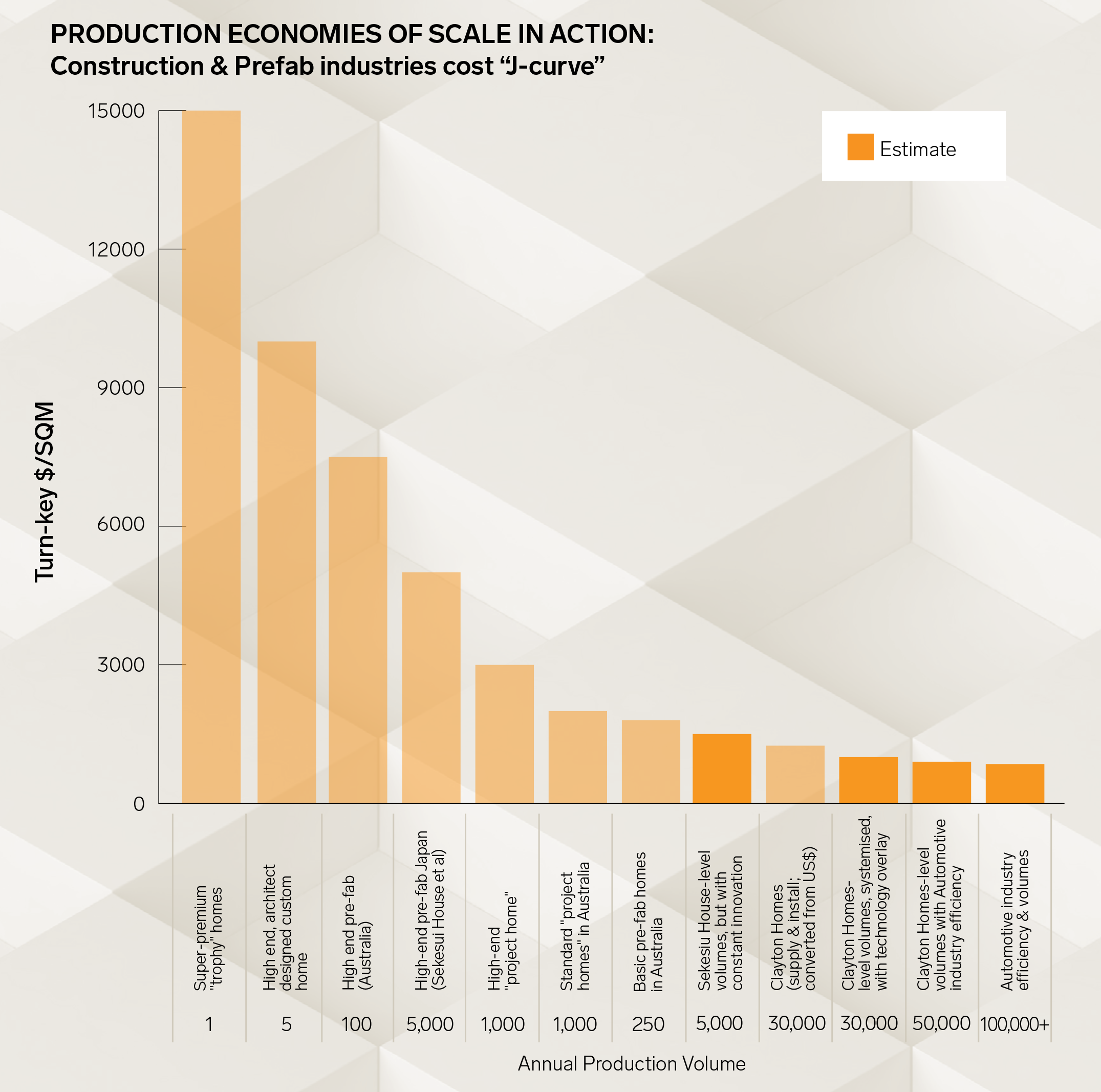

So where is the natural limit of cost efficiency in the context of prefabricated building? How far down the cost J-curve is it possible to aim?

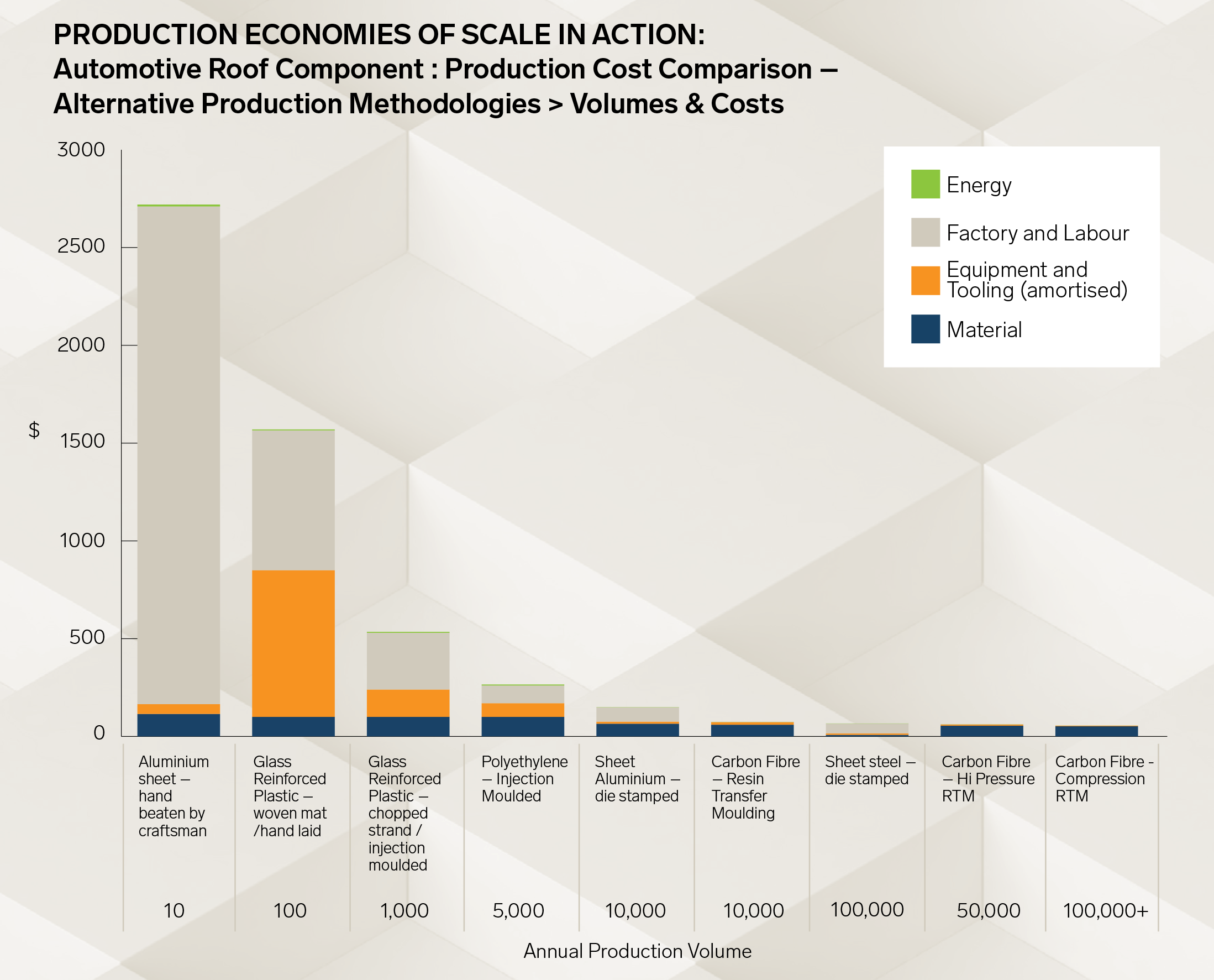

The benefit of overseeing the costs on hundreds of residential projects over the years, mapping volume/price points for the construction and prefab industries, demonstrates a remarkably similar ‘J-curve’ trajectory to automotive, which may allow a bit of 'what if' crystal balling in the construction industry version of the cost J-curve below. The high end, custom designed and master built homes showing on the far left of the curve are about as cost effective as the hand-beaten aluminum roof, or the hand-laid GRP panels, in the automotive chart.

The high end, custom designed and master built homes showing on the far left of the curve are about as cost effective as the hand-beaten aluminum roof, or the hand-laid GRP panels, in the automotive chart.

High end modular, in Australia, demonstrates how a factory made product, similar in quality to the high quality master built home, can be delivered for cost savings of perhaps 25% against comparable in-situ build, because of the efficiency in the factory and the somewhat repetitive nature of the prefab product on offer.

In Japan, high end modular products are comparable in quality to their Australian peers, but with savings in the order of 25% - 30% by comparison, because they have the volumes to drive the prices down.

High end 'project homes' and their 'low end' siblings again show cost savings in the order of 25% to 30% for each step change. The savings here are partly driven by the volumes being delivered and partly through the demonstrable reduction in the quality of the product, compared to those further up the curve. Lower end prefab manufacturers are comparable in cost to lower end project home products. While they both may have directly comparable quality, the smaller prefab operators achieve these costs with volumes <100 units per year, while the project home builders may require >1,000 units per year to get to this point. These are general statements for sure, and dependent on the specific quality intent of each builder; where the building sites are, and how easy to access, where the factories are, and so on, and there will be plenty of exceptions / outliers, but on average across the mainstream Australian market, identifying these players at that point on the curve will be generally reflective.

Further down the curve, Clayton Homes in the USA, as the umbrella group for Berkshire Hathaway’s conglomerate of brands, assembled in the immediate wake of the 2008 GFC, is a clear demonstration of how huge volumes can bring the price point down dramatically. Manufacturing in the order of 50,000 homes a year, in dozens of factories across the mainland, Clayton rolls out about 25 to 35 completed homes every week from each factory. They sell ex-factory for US$500 per square metre. With assumed transport and installation costs, this translates to perhaps AUD$1,250, turn-key.

While these prices are encouragingly affordable, it is worth noting that the quality of these homes is discouragingly low. They are robust for sure, with a basic steel chassis underneath, with timber stud walls and insulation adequate for the climate zone intended. But they are in every way basic. Fixtures and finishes would be deemed unacceptable in the context of the average Australian home. They are designed to a specific manufactured home park building code, with a very specific, albeit large, demographic in mind.

It is also worth noting that there is little evidence of manufacturing in the Clayton Homes plant. Production is reliant on large numbers of low wage workers, carrying out traditional construction work, within the factory environment. While they all benefit from Berkshire Hathaway’s formidable purchasing power, the factories are not huge. Each plant produces perhaps 1,000 to 2,000 homes per year, suggesting that it may not be necessary to produce 50,000 per year to realise most of the volume based efficiencies.

Where then could a systemised, modular product, with high levels of production engineering and modest levels of capital investment get to?

While it may be crystal balling, those “What if?” price points shown at the lower, flatter end of the prefab J-curve should at least be achievable in theory. It may not be aspirational to populate the world with ever more Clayton Homes type product, but perhaps the most exciting spot on that curve is the “Sekesui House-level volume, but with constant innovation”. If Sekesui, or

a newer entrant to the market, like a reasonably well funded Australian player, were to be free of the crushing constraints that a billion dollar factory placed on its ability to innovate, and to bring on new materials and methods with each step change in volume, then what would that volume-price point look like?

The actual automotive J-curve, and the extrapolated prefab J-curve point to where an innovative, agile modular manufacturer could provide high volume, top-shelf product – comparable in quality to the “High end, architect designed custom home” - for a turn-key price in the order of $1,500 per square metre. Equally, the J-curves also suggest that a product to rival traditional entry-level ‘project homes’, could be delivered for a turn-key cost of $800 per square metre, if manufactured in sufficient volume.

Notably, MGI's 2017 report suggests the key areas for improvement are the use of digital technology, new materials, and advanced automation, and concluded:

Notably, MGI's 2017 report suggests the key areas for improvement are the use of digital technology, new materials, and advanced automation, and concluded: While this approach might half completion of an individual bathroom, real time benefits are provided at a higher level in the overall schedule. Beyond the elimination of unnecessary float, the secret to effective time compression in any program is to identify those tasks that don’t have (or can be tweaked not to have) dependencies on prior tasks. The key is to start every task as soon as possible, run as many tasks as practically feasible in 'parallel' not in in 'series'.

While this approach might half completion of an individual bathroom, real time benefits are provided at a higher level in the overall schedule. Beyond the elimination of unnecessary float, the secret to effective time compression in any program is to identify those tasks that don’t have (or can be tweaked not to have) dependencies on prior tasks. The key is to start every task as soon as possible, run as many tasks as practically feasible in 'parallel' not in in 'series'. While house-building may not ever reach the volumes suggested here for the electric vehicle at 90,000 units per year, the inference is clear – there are dramatic savings to be realised through volume manufacture.

While house-building may not ever reach the volumes suggested here for the electric vehicle at 90,000 units per year, the inference is clear – there are dramatic savings to be realised through volume manufacture.

Volkswagen’s MQB – ‘Modular Transverse’ – multi-brand product platform

Volkswagen’s MQB – ‘Modular Transverse’ – multi-brand product platform The high end, custom designed and master built homes showing on the far left of the curve are about as cost effective as the hand-beaten aluminum roof, or the hand-laid GRP panels, in the automotive chart.

The high end, custom designed and master built homes showing on the far left of the curve are about as cost effective as the hand-beaten aluminum roof, or the hand-laid GRP panels, in the automotive chart.